MURDER, POLITICS, AND THE END OF THE JAZZ AGE

by Michael Wolraich

Perhaps the most appropriate way to celebrate Labor on its weekend is

to work. My work is

academic in nature, so here goes.

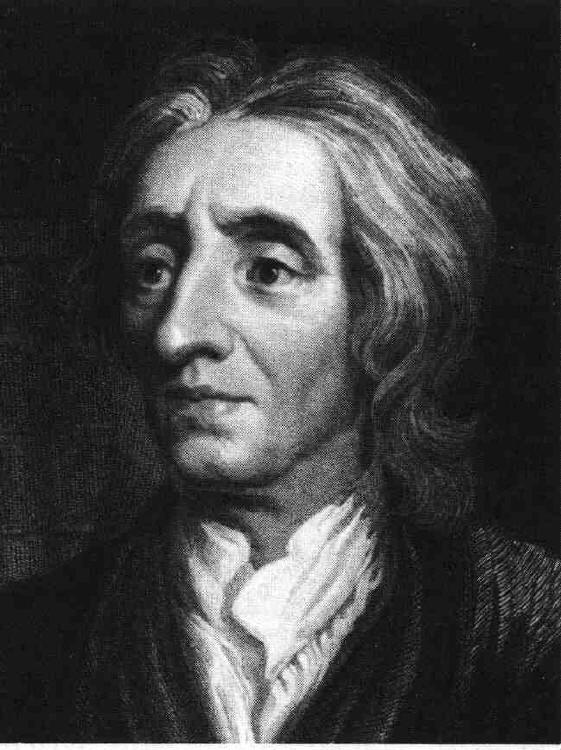

I start by introducing someone who probably needs an introduction, especially to those who misuse him constantly, the English Enlightenment Philosopher, John Locke. Locke is presented by the right as the ardent defeneder of the rights of property, which rightists go on to define in ways which Locke would hardly comprehend. These rights have their basis not in Nature or Natural Law, but in Labor, protected by Civil Law. Locke's contributions rest in his two Treatises on Civil Government: most particularly in the second treatise. I'm working hard so you won't have to: but I'll provide links of reference so you can play with this if you have a mind to. The most significant sections for my discussion are Chapters II ( Of the State of Nature) and V. (Of Property), VIII (Of the Beginnings of Political Societies) and XI (Of the Extent of Legislative Power). There are useful things elsewhere, for example Chapter IV absolutely condemns slavery, which is why Jefferson had to fiddle with Locke in order to make him useful in the Declaration of Independence. But while I'm willing to work fairly hard, I'm not willing to work beyond the patience of at least a few readers, so I hope I'll be excused if I don't go into detail, chapter and verse. Speaking of chapter and verse, the sections in the Treatise are numbered consecutively without regard to chapter division, which should make it reasonably easy to follow me around.

|

|

| John Locke

as the Right Wing sees him |

John Locke

as he was in real life |

1. The Common Weal.

How many states does the United States have? Forty-six. No, I haven't slept through the addition of New Mexico, Arizona, Alaska, and Hawaii. Massachusetts, Pennsylvania, Virginia and Kentucky are are Commonwealths. [Full disclosure: in my first draft I remembered only Massachusetts and Pennsylvania, which points to the usefulness of a second pair of eyes and an additional brain. Thanks, friend that I've never met.] The term is important to Locke, and should be important to us as well. Common has two meanings, one of which sounds a bit, how shall I put it, less than excellent. "How common of him," says Lord Snobbe. The crucial meaning for Locke is the other one...that which is held in common by the community as a whole. This is, of course what common schools are, though the way people take an axe to public education these days, I'm not sure they mean to refer to them in the Lockean sence of the word. The Boston Common is a pretty grand place. Who "owns" it? All the Boston Citizens.A state also of equality, wherein all the power and jurisdiction is reciprocal, no one having more than another, there being nothing more evident than that creatures of the same species and rank, promiscuously born to all the same advantages of Nature, and the use of the same faculties, should also be equal one amongst another, without subordination or subjection, unless the lord and master of them all should, by any manifest declaration of his will, set one above another, and confer on him, by an evident and clear appointment, an undoubted right to dominion and sovereignty. (Section 4.)

Locke is an empiricist. He sees no "manifest declaration," no Divine Right of Kings. (Which is why he spent so much of his life in exile). So we're equal in rights. Equal in Liberty.

The empasis is mine, and I add it because the sequence is crucial to understanding Locke. Possessions is last on the list for a reason, the common possessions of the others takes supremacy: indeed, without the prior, in the sequence stated, the latter is meaningless. So, as I hope to show, Locke's philosophy maintains protection of the common health essential to the commonwealth.

Now Locke wrote sentences longer than some of my students' papers. That was the style back in his day. We don't read the way he wrote, so I hope I'll be pardoned if I provide a bit of a sentence to further my argument. The bit is seventy words long itself:Take that, Bernie Madoff. Take that as well, violators of Labor's rights.

In nature, very little. Rights are civil artifacts, created by governments to protect the commonwealth. Government and the common good or weal are not the same things, which is why Locke finishes with a defense of the idea of revolution and dissolution of government. One doesn't have jump to the end of the treatise to see where he's heading, however.

The Right Wing likes to quote one specific Locke maxim from Chapter IX: "Sec. 124. The great and chief end, therefore, of men's uniting into commonwealths, and putting themselves under government, is the preservation of their property. To which in the state of nature there are many things wanting." This section is shorter than the half sentence I quoted immediately above. That makes it very easy to quote, very easy to remember, and very essay to take out of context and all three of these "very"s make it very useful to those who think property is the be-all and end-all. But one can't consider this without considering the context. So let's do that very thing, starting with the connection to the origins of civil society itself-which is where the rights idea come in.THE great end of men's entering into society, being the enjoyment of their properties in peace and safety, and the great instrument and means of that being the laws established in that society; the first and fundamental positive law of all commonwealths is the establishing of the legislative power; as the first and fundamental natural law, which is to govern even the legislative itself, is the preservation of the society, and (as far as will consist with the public good) of every person in it. This legislative is not only the supreme power of the common-wealth, but sacred and unalterable in the hands where the community have once placed it; nor can any edict of any body else, in what form soever conceived, or by what power soever backed, have the force and obligation of a law, which has not its sanction from that legislative which the public has chosen and appointed: (Section 134).

Sec. 97. And thus every man, by consenting with others to make one body politic under one government, puts himself under an obligation, to every one of that society, to submit to the determination of the majority, and to be concluded by it; or else this original compact, whereby he with others incorporates into one society, would signify nothing, and be no compact, if he be left free, and under no other ties than he was in before in the state of nature. For what appearance would there be of any compact? what new engagement if he were no farther tied by any decrees of the society, than he himself thought fit, and did actually consent to? This would be still as great a liberty, as he himself had before his compact, or any one else in the state of nature hath, who may submit himself, and consent to any acts of it if he thinks fit.

4. My Property is, first and foremost My Labor.

What turns common property into private property. Work. In other words, Labor. Locke's reasoning is very interesting to me. He begins with the idea which make slavery inestimably wrong in his view. No matter what else, we have "property" in our own persons. We own ourselves, and that being the case, two things obtain. First, we can do with ourselves what we wish, subject to restrictions against self destruction. Second, through our ownership of our persons we own our work-our person in action. Locke is a contemporary of Sir Isaac Newton and the physics we call Newtonian. He understands work as force applied across time. (More about that later). It is the work involved which transforms common property into private property. "Whatsoever, then, he removes out of the state that Nature hath provided and left it in, he hath mixed his labour with it, and joined to it something that is his own, and thereby makes it his property". (Section 26).He that is nourished by the acorns he picked up under an oak, or the apples he gathered from the trees in the wood, has certainly appropriated them to himself. Nobody can deny but the nourishment is his. I ask, then, when did they begin to be his? when he digested? or when he ate? or when he boiled? or when he brought them home? or when he picked them up? And it is plain, if the first gathering made them not his, nothing else could. That labour put a distinction between them and common. That added something to them more than Nature, the common mother of all, had done, and so they became his private right. And will any one say he had no right to those acorns or apples he thus appropriated because he had not the consent of all mankind to make them his? Was it a robbery thus to assume to himself what belonged to all in common? (Section 27).

Locke expects a "yes" to his rhetorical question. Herein, I think, one finds the core of the Labor Theory of Value. Perhaps Marx had a copy of Locke at his chair at the British Museum. The kind of property the above creates we call "personal"-in that we can pick it up and carry it around with us, at least in person. The common from which it comes can be left behind.5. You can't have it all, even if you want it all.

I've mentioned some of the restrictions on property rights above. I'd like to return to that theme for a bit. Locke couldn't imagine a world fully populated, bursting at the seams. Six billion of us now, with likely Nine Billion of us by 2050 would have been incomprehensible at a time when the population of London was under 500,000. (At the time of the American Revolution, no American city had more than 25, 000 persons living in it. Philadelphia took the prize for hugest...New York was not even the big crab apple.) But he still had a caveat on the amount of personal property a person could morally appropriate.Locke knew, of course, that money solved the problem of the objection above, or maybe one of the problems above would be a better way to put it. Money, specie, things which Locke defines as "things that fancy or agreement hath put the value on, more than real use and the necessary support of life" (Article 46) stored the value of the perishable in an imperishable substance. But even here, the value is social. This stuff is valuable to the extent that the commonwealth agrees it is valuable. Moreover it is valuable because it is scarce, if not particularly usable. (Locke might have to modify his assessment in the electronic age. Gold and silver are usable in ways he couldn't have imagined.) One of the fanciful qualities is scarcity. Gold, silver and diamonds were valuable because they were not readily available and were easily transportable. Sand would make a crummy specie.

It's not necessary to say much on this point, thank goodness. Two points will suffice. First, creating real private property does diminish the commons in absolute terms. Locke recognized that this resource was finite. When he wasn't living in exile for his radical views he lived on an Island, and a not very big one. England was very much a country of shires (without Hobbits, alas) and in Locke's era traditional commons were being being converted into large private land holdings. The process dated back at least to the time of Sir Thomas More, and resulted in much rural unrest, to say the least. Economists have debated whether the conversion ultimately benefitted society-with the larger holdings being more efficient. Most recent analyses seem to think not, or if so, not much. Locke argued against allowing the commons to disappear through the domination of private interests.

Second, even on those lands in private hands the public interest prevailed. Right of real property is more a right of exclusion, by which one can keep others from using one's real property. Keep out of my yard! Go play at Home! But at the same time cannot do anything with his/her property he/she wishes. Consider zoning by use, for example, or laws against creating a public nuisance.In a nutshell, because it is scarce. We're mortal. "The cliche is time is money," and the image is Boss Greedyguts standing with one eye fixed on the stopwatch, the other eye on the workers, and the foot tapping impatiently, Taylorizing everyone. But time is less money than life itself. My "sand" is more like the sand of the hourglass than the sand of the seashore on the beaches of a thousand universes. Would work be as worthy of dignity if we were immortal? I don't think so and neither does John Locke. I use time and ultimately use it up. This is what makes my work worth something-to me, if to no-one else. The force I exert across time, that's my work, my labor. So today we celebrate that...celebrate life itself by celebrating labor. Locke would understand that.

Thank you for recognizing that, John Locke.