When Francis Bellamy wrote these words toward the end of the nineteenth

century,

his

goal was not so much to present a loyalty oath to the nation itself,

as an homage to "the republic for which [the flag] stands." What

follows is neither a brief for or against the pledge, nor the oxymoronic

addition of an expression of religious sentiment in a nation founded on

lands settled by people fleeing religious intolerance. It raises the

question which Bellamy, no doubt, hoped to help settle in 1892 not yet

thirty years after the civil war but one which, it seems certain today,

has not been resolved almost 150 years after that war ended. To those for whom history begins anew every week or whose recognition of

the events which make up our collective wisdom includes only those

matters of which they are personally familiar, the "tea party" people,

the obstinate Republicans in Congress, FOX News and all the others with

whom we live who refuse to acknowledge the election of President Obama

or have determined to oppose any thing he proposes, are something new.

To the rest of us they represent the divisions which have existed since

before it was decided to declare independence from Great Britain by

pledges

of "our lives, our fortunes and our sacred honor".

What

brought all of our forebears together was, of course, the desire of the

self-proclaimed "free and independent" states to a new government rather

than continue to be subject to

repeated injuries

and usurpations, all having in direct object the establishment of an

absolute tyranny over these states.

Beyond that

point of agreement, however, there were many issues upon which these new

states did not agree. It took well more than a decade before the

states could agree on any sort of truly unifying government

"to form a more perfect

union" and, for all intents and purposes, the Civil War and its

resultant Fourteenth Amendment for the national government to be able to

impose on the states the obligation not to

make or

enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of

citizens of the United States; nor ... deprive any person of life,

liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person

within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.

As

we have learned many times since then, though, requirements imposed on

others by force of arms do not always take hold. The same "United

States" rent asunder by all things related to slavery existed before and

after the Civil War. That the best those against slavery could

accomplish In Congress prior to the war

was the sort of

standoff absurdly referred to as "the Missouri Compromise" would

have prevented anything like the Fourteenth Amendments (and the

Thirteenth and Fifteenth, as well) but for the fact that the former

confederate states were under military occupation and unable to stymie

Congress as it had before the war.

The cleavages are certainly

mot as deep as they were then, but they have not been materially altered

even today. The old "2/3rds rule" which gave southern states

extraordinary control over the presidential nominees of the Democratic

Party until

President

Roosevelt's New Deal popularity in the party permitted him to get rid

of it in 1936 was probably the most significant vestiges of that

continued division until the filibuster as a means to prevent civil

rights legislation became a popular device in the late 1950s and into

the 1960s. It required the murder of the President of the United States

to shock Americans into realizing that we were still hostage to the

national divisions predating the civil war and permitting, in our grief,

the breaking of the filibuster long enough to get the Civil Rights and

Voting Acts to a President's desk.

But grief, just as the

circumstances of those vanquished in war, does not change fundamental

differences; at best it provides the opportunity to ignore the

complaints of the minority. Ignored, they chafe at what is forced upon

them. They never accept it.

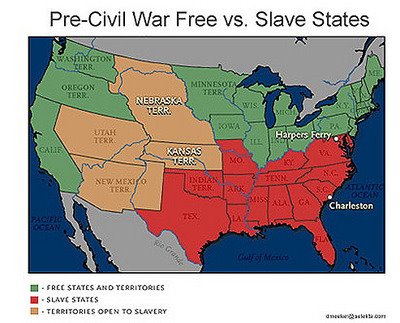

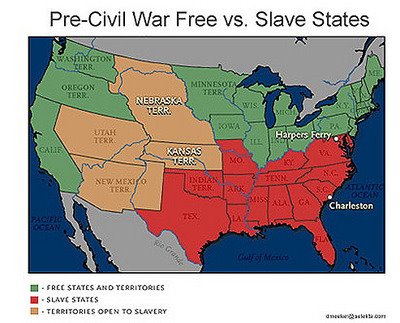

The famous comparison of the

nation's

slave

and free divisions prior to the civil war,

with

the

electoral map of 2000

proves the point almost as well as this

week's contretemps when the Governor of Virginia,

proclaiming

this month to be dedicated to the memory of the Confederate States of

America insisted that the war to establish that new nation was

engaged in by

leaders and individuals in the Army,

Navy and at home who fought for their homes and communities and

Commonwealth in a time very different than ours today

The

Governor was, of course, forced to back down and

to

amend his proclamation to agree that it is also

important

for all Virginians to understand that the institution of slavery led to

this war and was an evil and inhumane practice that deprived people of

their God-given inalienable rights

but, again, the

required adoption of the views of a majority does not change his view or

that of millions of our fellow citizens who do not accept the

underlying premises that, for instance, black people are entitled to the

same rights as those who are white.

It goes much deeper than

that, of course, but keep this in mind: these people will never accept

that a person whose father was black and who appears more of that race

than that of his mother could be President of the United States. They

view the Civil and Voting Rights Acts as the spoils of war, not to

mention the Fourteenth Amendment: perhaps binding law, but

illegitimate. Many of them feel to still be under sort of an occupation

by the victorious forces in the Civil War and that is why they want to

continue to celebrate the few years when they were able to maintain

their own government in rebellion.

While these forces had a

stranglehold on the Democratic Party until first, the abolition of the

"two thirds rule" and then, finally, the enactment of the Civil and

Voting Rights Acts sent them to the Republican Party, their control of

their "new" party is far more absolute. Even at the height of their

strength in the Democratic Party they could not prevent the nomination

of New York Governor Alfred E. Smith, a "wet" Catholic,in 1928, although

in retrospect, it is absurd to think such a person could have been

elected president then. Today, though, the Republican Party could not

nominate anyone who doses not subscribe to the same "way of life"

euphemisms which have been used to paper over the fundamental

differences which have existed among our citizens since we first decided

to join forces in revolution against the Crown.

This is what we

are up against, my friends. Change this and we will have changed

history forever. It seems inevitable that that time will come, but at

233 years and counting, you have to wonder.