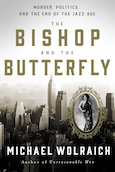

MURDER, POLITICS, AND THE END OF THE JAZZ AGE

by Michael Wolraich

Order today at Barnes & Noble / Amazon / Books-A-Million / Bookshop

|

MURDER, POLITICS, AND THE END OF THE JAZZ AGE by Michael Wolraich Order today at Barnes & Noble / Amazon / Books-A-Million / Bookshop |

. "»

J. Bradford DeLong on February 01, 2014 at 12:22 PM | Permalink | )

From the London School of Economics's excellent Politics and Policy weblog:

And misleadingly titled--it's not five, but more like forty:

Five minutes with Angus Deaton:

Joel Suss: Your new book is titled “The Great Escape: Health, Wealth and the Origins of Inequality”. What is the great escape? What are the origins of inequality?

Angus Deaton: The great escape is two things: First, it is one of the basic movies that everybody knew and everybody watched in which some people break out of a German prisoner of war camp in World War II and, you know, they are very sophisticated and they dig tunnels and they make passports and fake documents and all this. And then more than 200 people get out through these tunnels and head for home. Not very many of them make it, which is something we might come back to but it was the great escape. So I use that as a sort of running analogy for the real great escape of the book which is people escaping from a sort of prison of early death, destitution, having very little – living as slaves, no democracy, no education. All the things we take for granted today, at least in some of the world, people didn’t have and so they’re escaping to freedom from the sort of “unfreedoms” of those things.

Joel Suss: The fact that some have escaped necessarily creates inequality, you point out. So the fact that there’s inequality shows that progress is happening for some. You also discuss the ‘dark side’ of inequality.

Angus Deaton: It’s complicated, right? Because it’s not, in the first instance, just bad. I mean, you don’t think that the people who got out of the prisoner of war camp made it that much worse for the people that were in. But let me give you an analogy which I think shows the ambiguity of the problem. In 1964 there was a very famous report in the United States by this surgeon general which was the first to many Americans definite evidence that smoking was really bad for your health. And, you know, that saved a lot of lives because people, they made their escape from addiction to cigarettes because they knew this new information. But one story I tell in this book is that this surgeon general, who’s a gentleman called Luther Terry, was chain smoking on his way to the press conference where he was going to introduce the surgeon general’s report. His aide was sitting next to him in the car and said “Dr Terry, I should prepare you for this, you’re not going to like it but the first question you will be asked is ‘do you smoke’?” and Luther Terry says “that’s ridiculous! That’s a private question, that’s nothing to do with public health”, you know, how dare they? And the aide said “Well, you know, I’m just telling you” and the first question was “Do you smoke” and Luther Terry said “No, I do not smoke” and they said “When did you quit?” and he said “20 minutes ago!”

Turning that story on its head; here’s the surgeon general, he’s a physician and quit within 20 minutes of his own report. Most physicians quit pretty quickly after that too. Most educated people followed. Most wealthy people followed. So then what you had was the people left behind. Now you don’t think that’s bad because you know, OK a lot of people did better, no one’s worse off that they were before, why is the world a worse place? But 50 years later when those inequalities are still there does that seem such a good thing? There’s some structural inequality there which is very – seems very hard to erase and it seems morally very ambiguous. So that’s one sort of inequality that seems really problematic. There are many others.

Joel Suss: In your book you say that inequality perpetuates itself, especially when the very rich have no stake in public health or public education. Can you elaborate on that a bit more?

Angus Deaton: So that’s the dark side of inequality. On the bright side, if the returns for going to school go up then there’s a big incentive to go to school and that brings you up and that seems terrific. On the other hand if you don’t have the talent to go to school you get left behind and there’s nothing you can do about it. And that sort of inequality doesn’t seem like such a good inequality and the people who don’t have that talent are relatively worse off than they were before. But the really dark side is what you just talked about, which is this issue when you get extreme income inequality and these people that are very very wealthy. They’re so wealthy they hardly need any government. They don’t need government education, they don’t need healthcare, they may not even need the police or the law courts because they can buy lawyers and policemen or whatever. They’re relatively independent of these things that the rest of us really need and so they have no interest in paying taxes. So it’s very much in their interests to undermine the provision of public goods.

You know the government shutdown that recently ended in the United States? The fact that it was fought over the healthcare extension, and the fact that that strategy was developed wealthiest people in the United States is a very good illustration of the sort of themes I’m talking about.

Joel Suss: You are concerned about the future of democracy because of this growing inequality. Can you elaborate on this?

Angus Deaton: I think it’s worse in the United States that it is in the United Kingdom because of the pervasive importance of money in politics. But the lobbying that’s become very important in the United States is not just the buying of politics, you can do that anywhere. I think it’s much less important in the UK still, but, before Brits get too complacent about “this would never arise here”, it didn’t use to be very important in the United States either. There’s been an enormous increase in it. In fact the real problem from an economist’s point of view is why isn’t there more of it? Because the rewards for lobbying can be ginormous and the cost of lobbying is way smaller than the rewards so why isn’t there a lot more? I think Gordon Tullock was the first to raise that question of why isn’t there more money in politics? That’s the real puzzle. Basically if the rich can write the rules then we have a real problem.

A couple colleagues of mine have recently written books in which they studied voting patterns in the US Congress and matched them up with the preferences of the constituents of those Congressmen. And they’re very closely aligned with the preference of their wealthy constituents and not at all aligned with the preference of the poor constituents. So there’s a real movement of democracy in the direction of plutocracy and that is something to worry about. On the other hand I don’t think the game is over yet. We may or may not already be at half time or something. If you think about the last election in the United States, one of my favourite stories is that, you know the plutocrats really thought they’d won and they had bought enough polls in pleasing direction to believe themselves that Romney was going to win. Apparently you could not park your private jet in Boston because every fat cat in the country who contributed to the Romney campaign had parked there for the victory party, which of course never took place. So that’s a case where the money did not overcome democracy in that way. And so, the more recent crisis is some attempt to come back at that and so there’s an endless battle over those issues going on but I don’t think we’re done yet.

Joel Suss: The book focuses on two aspects which are important for “the good life” which you say are material well-being and health – why do you look at these together?

Angus Deaton: Because I think you make a terrible mistake if you don’t. My regret is that I don’t know enough or couldn’t write a big enough book to bring other aspects of freedom in there like democracy, education, the ability to migrate, for instance, which is something I don’t really talk about at all and I think is very important. We’ve become very specialised, so economists are left to think about income, doctors left to think about health, and political scientists to think about politics. “That’s your business, this is my business” sort of idea. But if people get richer but they’re totally disenfranchised, that doesn’t seem like such a good deal. If people get richer and their health gets worse, or someone else’s health gets worse as a consequence of them getting richer, it doesn’t seem like such a great idea either.

Even in just the most mundane policy planning, health is becoming more and more expensive, so people are developing cures for cancer but they involve drugs that cost the earth. Are we going to give those to people? If you’re in Britain that would be paid for collectively. But there’s a real cost, so do you really want to, you know, give up people’s pensions for example in exchange for a few months extra life from leukemia for instance? There are some real hard choices there to be made there and you can’t think of them as, you know, “we should just do everything we can to extend people’s lives” or “we should keep people as rich as possible”.

Joel Suss: Now that the top 1% or top .1% continue to amass an ever greater share of society’s wealth – where are we headed? Are you pessimistic or optimistic?

Angus Deaton: The future is enormously hard to predict, as you know! I think there’s a lot of danger and some days I’m pessimistic and other days it seems like…there are forces on both sides of this and you know, people don’t really like being messed around with. One thing we haven’t talked about is the slow down in economic growth in the United States and other rich countries too, and I think that makes all of this that much more poisonous because if the pie’s growing you can give people extra slices without hurting what you have. But when the pies not growing, the only way I’m gonna get something is by taking away from you guys.

Joel Suss: In your new book you write that “foreign aid is doing more harm than good and it is undermining countries’ chance to grow”. Can you explain your argument?

Angus Deaton: The dominant fact for me about most poor countries is that the social contract, the contract between the government and the governed, is not there. It’s very weak and it’s very unsatisfactory and you know in many cases the government is preying on the people, not helping them. It’s what you call an extractive regime rather than a sort of helping, promoting regime. The problem is that if you’re in a country, say in Africa, where there are pretty weak institutions to begin with and you bring in a lot of foreign aid so that the leaders can run the country without ever consulting the voters or the public.

We have also got ourselves into the situation where the donors have to give money even more than the guys have to receive it. Because guys at the World Bank don’t get paid if they don’t shift the money! I think it’s much the same in the UK’s Department for International Development (DFID). I think they have very strong incentives to keep the aid flowing. Of course the people receiving it know that very well and they can behave badly and with impunity. I think that really does make this contract very fragile.

Let me clarify just a little bit though, the real point in my argument is that that mechanism is always there if you’re taking money into the country. It doesn’t mean that you wouldn’t necessarily want to do it if other things are strong enough. The strongest case is possibly that there’s millions of people alive today because of anti-retrovirals who’d otherwise be dead, and those are paid for by foreign aid essentially. Saving those lives counts for a lot, and maybe undermining the government in those circumstances is OK – but your still undermining the government so that’s really what I want to pay attention to.

And finally, “aid”, it’s become clear to me, is used in very different senses. So for instance, if we were in the United States or you here were to develop a new pharmaceutical that made it much easier to deal malaria. Some people would count that as foreign aid. But it doesn’t fall into my definition. My argument is to do with giving money to the country and undermining the government. You don’t do that when you invent a cure for malaria or a vaccine for HIV/AIDS.

Joel Suss: Could you create conditions for the aid money that goes in? Ensure that it is focused in a way that improves upon or establishes institutions that aren’t there?

Angus Deaton: Well that’s the counter argument, I was at DFID recently and they were actually much more receptive than I thought they would be. Many of these arguments are fully familiar to them, which tells me that it’s a very good aid agency. They’re people who don’t have their heads buried in the sand.

People say, ”we’re working really hard to improve institutions”. I’m a little bit sceptical that people from the outside can improve the institutions that a country should have. I give an example in the book of how would Americans react if the Swedish government came and said “we’ll pay for medicare for the next 50 years but you’ve got to legalise gay marriage and let all black people out of jail”. Of course when I was at Princeton I said that and everybody in the room said “I’ll go for that”. But the majority of Americans really would not be so keen on that.

There really is an issue about undermining sovereignty, especially in situations where the country may not have all that much choice. But on conditionality, I would love it, I think that conditionality would be great if you could make it stick but it’s just not credible because the inconstancy problems: once they misbehave you don’t actually want to do it. And secondly because there’s not just one aid agency, there’s thousands of them and if you don’t get it from the US you can get in from Germany or from Britain or from Australia – or in the end you can get it from China.

Joel Suss: In your book’s introduction, you say: “Those of us who were lucky enough to be born in the right countries have a moral obligation to reduce poverty and ill health in the world”.

Angus Deaton: The moral obligation is important because I don’t want it to sound like I’m a heartless bastard who has no interest in this partly because there’s just this: these people are hurting and if you can help them you ought to help them. Secondly, some of their hurt is to do with us, you know the colonial programme was not a great success. It might have been a great success for the Brits, it was not a great success for what happened in India. So we owe them big.

I have students I meet at Princeton who come to me and say “I want to devote my life to making the world a better place” and “I want to dedicate my self to reducing global poverty” and I say there are two ways: one is impossibly hard but I know at least one person who did that, some other people have done it. You go to Sierra Leone, you go to India or wherever. You become a citizen, you use your skills to help local groups agitate. You don’t take any money from outside, you just become like them and you use the skills and knowledge you’ve learnt here to help them. My friend Jean Drèze is an activist in India who’s been incredibly successful in doing this. He had to renounce his Belgian citizenship, it was very hard for him to even get that done. He lives without money because he’s frightened of being compromised by that and he’s been enormously successful. But it’s like the camel going through the eye of the needle right? It’s hard.

The other thing I tell my students to do is go to Washington and tell them to stop selling arms to poor countries. These are very very articulate smart kids who are going to be national leaders and god knows what else. You may not think you have much power now but you really do – go and get high positions, go and put pressure on these bastards to stop doing this. There’s a lot of stuff about aid but not that much publicity for debt relief. What about publicity about Britain selling arms? Fighting on those causes is something that people in our, rich countries have the legitimacy and standing to do because they’re citizens of those countries.

Joel Suss: Will the ‘Great Escape’, the recent exiting of many people in the world from the scourges of poverty and ill health, have a happier ending than the movie that inspired the metaphor?

Angus Deaton: I hope so! I think that I say that there are real threats there, global warming being the most obvious. But there are lots of political threats, from China, from the US. Things could go badly wrong. Bad politics has a long record of destroying human progress for long periods of time. So you want to worry about that. If you were a clear-eyed, reasonable but sceptical person you might easily think that this 250 years of progress could be just a flash in the pan, like what happened in China in the 11th century.

However, I think people always want to make the great escape and even if you have terrible setbacks, you can fill in all the tunnels but you can’t stop people knowing how to dig tunnels. Maybe you can eventually, maybe if you went back into the Stone Age people would forget how to forge documents or whatever you need to do to get out. But there’s an asymmetry there, which if you build some project and you don’t tend it the roads get all weeded up and you can’t use it after a while. But the knowledge that boiled water is safer than not boiled water is not going to evaporate in five minutes. Even if the world came to an end and we were all wandering around my mother would still be telling me to wash my hands

The intra-Palestinian meeting in Moscow has precedent

— Hanna Notte (@HannaNotte) February 29, 2024

Russia's hosted such meetings in the past, most recently Feb 2019

Russia has long lamented the US' "monopolization" of the peace process & tried to carve out a niche for itself: mediating among the disunited Palestinians/2

Here's what I told them: https://halginsberg.com/vote-for-jill-stein-again/

Controversial Brazil law curbing Indigenous rights comes into force https://t.co/pCoDg05irX

— Gareth Harris (@garethharr) December 28, 2023

Location: U.S. Embassy and residential compounds

Events: Heavy gunfire is occuring around the area of the U.S. Embassy and residential compounds adjacent to the Trutier area of Tabarre. All Embassy personnel have been instructed to remain indoors and shelter-in-place until further notice. All others should avoid the area.

Actions to take:

- Avoid the area;

- Avoid demonstrations and any large gatherings of people;

- Do not attempt to drive through roadblocks; and

- If you encounter a roadblock, turn around and get to a safe area.

By The Editorial Board @ Bloomberg.com, December 8, 2023

A mass expulsion of Afghan migrants could destabilize the region and fuel radicalization. The West should pressure Islamabad to change course.

All eyes on #Chad right now

Chad has two internet trunks coming into the country: One from the Red Sea via Sudan; the other from Cameroon. Not possible for the totality of the country's internet network to be shut unless done centrally. A lot of rumors swirling; few facts. https://t.co/N6bDJZ2ixO

BREAKING: Three loss prevention employees in Macy’s across the street from Philadelphia City Hall stabbed, one of them has died from stab wounds, @PhillyPolice sources tell me. Police converged on the store as the three workers were rushed to Jefferson Hospital. pic.twitter.com/4U1eKycL4W

Former US Ambassador Arrested, Charged With Working As Secret Agent For Cuba https://t.co/LDwo4ZJI1K

— HuffPost (@HuffPost) December 4, 2023

[Chapter I news is HERE, Oct. 7 til today]

You don’t get it.

— George Deek (@GeorgeDeek) December 2, 2023

It’s not about an UNRWA teacher who held an Israeli kid hostage in his house.

It’s all about how for 75 years you have destroyed the future of generations of Palestinians, including my family.

My cousins in Arab countries are still not citizens - not even the… https://t.co/nv6anubGhc

Note 'Community Notes' attached to UNWRA's statement.

Imperialism for me but not for thee?

It's wild that Venezuela is now holding a vote on whether 2/3 of Guyana actually belongs to them! Analysts suggest that Modoru may want military action to pump up his sinking popularity.

Could we have a war in South America?!?

"The people who live in Essequibo are largely… pic.twitter.com/QvMEjkkgwy

The lack of a cohesive delegation has allowed attention-seeking lawmakers to act on their own.

McCarthy: “You have [Rep. Matt] Gaetz, who belongs in jail…”

Gaetz: “Tough words from a guy who sucker punches people in the back. The only assault I committed was against Kevin’s fragile ego.”https://t.co/LctPuz6Pcf

By Martinn Pengelly in Washington DC for TheGuardian.com, Nov. 30

Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez tells Ryan Grim life in Congress ‘completely transformed’ after Democratic leader stepped down

"Both the AU and the intl community place more weight on whether elections are held than whether they are free and fair. Sanctions/expulsions occur when there is a coup but not necessarily when elections are rigged or if an “institutional coup” occurs." https://t.co/m9dNimJP0D

— Cameron Hudson (@_hudsonc) November 28, 2023

Copyright © 2018 dagblog. All rights reserved.

Comments

The "Great Escape" model is interesting.

I particularly like the way Deaton framed his call to stop fueling local wars from a global/internationalist perspective. It is more common to hear those ideas expressed through the language of isolation and nonintervention.

by moat on Sat, 02/08/2014 - 5:29pm