MURDER, POLITICS, AND THE END OF THE JAZZ AGE

by Michael Wolraich

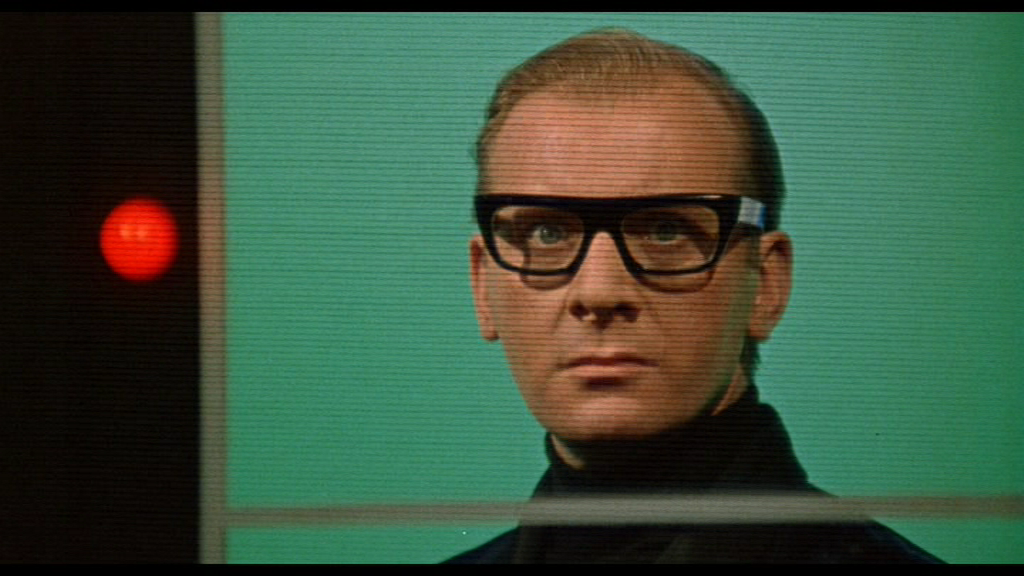

One of my fondest memories was showing Fahrenheit 451 to my stepson. After Guy Montag finds the community of living books at the end (of the film), my stepson proclaimed them heroes with the sort of ardor most kids reserve for famous athletes. He's a librarian now.

Named Mildred in the book, but called Linda in the film, Montag's wife spent her day between three viewscreens trying to please the arrogant, haughty people on those screens. The people on screen carry on a silly discourse, but occasionally turn to the camera and ask, “What do YOU think, Linda?” in an arch, affected tone. If she supplies an acceptable answer, they smile and say nice things about her. Despite all this drama, Mildred/Linda calls them her "family" and longs for Guy to earn more money so she can buy a fourth screen.

Ray Bradbury once said that Fahrenheit 451 was less about government banning of books than about people turning to entertainment, but the family does put me in mind of social media. I was reminded of the 451 family while reading answers to questions about secrecy, privacy and the transparency of the internet posed by computer entrepreneur Danny Hillis at The Edge.

The question of secrecy in the information age is clearly a deep social (and mathematical) problem, and well worth paying attention to.

When does my right to privacy trump your need for security? Should a democratic government be allowed to practice secret diplomacy? Would we rather live in a world with guaranteed privacy or a world in which there are no secrets? If the answer is somewhere in between, how do we draw the line?

I am interested in hearing what the Edge community has to say in this regard that's new and original, and goes beyond the political. Here's my question:

WHO GETS TO KEEP SECRETS?

These are quotes from longer replies. There are many other responses and more came in while I was at work today:

GEORGE CHURCH

Professor, Harvard University, Director, Personal Genome Project

Privacy is a relatively new social phenomenon. When our ancestors died in the tiny village of their birth, lacking walls, and surrounded by relatives, there were no secrets.

Privacy vs security is a false dichotomy and the answer may not fall between those poles.

Secrecy is false security. The memory hole of Orwell's "Nineteen Eighty-Four", a purposefully disingenuous illusion of information security, is not so fictional (e.g. old personal web searches revived in crime investigations). Add to that mathematical tricks, human error and willful individuals and teams, and we see strong arguments against dark secrets with nowhere to hide.

Secrets are symptoms — not demanding a better bandage, but a treatment for the underlying disease causes. AIDS created an activism that lead to open discussion and to less stigma associated with sexual preference. Even the apparent "essentiality" of secrets for police and war-fighters is symptomatic of a failure of diplomacy and a failure of technology policy to provide a decent life for all.

DOUGLAS RUSHKOFF

Media analyst; Documentary filmmaker; Author, Program or Be Programmed

I used to say that the net was preparing us for a future when we are all connected, anyway. That we will eventually become a biologically networked organism, where we will all know each other's thoughts. That the net was a dry run, a practice session for this eventuality. Now, however, I think that's the way we have always been. The privacy we have experienced in our lives and world has been like those Japanese paper walls. We hear everything going on behind them — we simply act like we don't, and sometimes we believe it ourselves.

I read the Church and Rushkoff answers and wonder if the internet social media, and Mildred's family, hearkens not to the future, but to a past where we lived intimately close with few secrets rather than privately apart. Privacy now seems necessary for survival, but people wanting intimacy reveal all sorts of damaging information on Facebook.

ANDRIAN KREYE

Editor, the Feuilleton (Arts & Essays) Section, Sueddeutsche Zeitung, Munich/Germany

... the answer used to be simple — individuals get to keep secrets. For institutions they should be the exception. ...

The real shift in the nature of secrets has come for individuals though. The Internet has become the most pervasive technology in the history of mankind. In a matter of one and a half decades most of mankind and it's institutions have developed an unprecedented dependency on a technology, which will have societal implications we are not able to fathom just yet. Most effects of the Internet are indeed benign, if not beneficial. Even if we lose control over our secrets, this might not be just a bad thing after all. But even though the jury is still out on this, one thing is for sure — most effects of the Internet are inevitable.

Take the debate about Google Streetview that has been nowhere as heated and dogmatic as in Germany. Opposition was so strong that Google Germany had to allow people to have their building pixilated. The reasons for the fervor in this German debate are quite simple. In a country where the lack of privacy and secret apparatuses where the mainstays of two disastrous dictatorships in the past seventy years alone, even a new step in cartography is perceived as an threat.

I have to wonder if the internet is as inevitable as Kreye says when A - most people have to pay for access and B - the middle class is in decline. With high unemployment, it is easy to assume that a significant number are off the internet now. If energy depletion takes hold, I would expect internet access to be the province of a steadily shrinking elite. Someday, the rest of us might actually have to talk to each other.

JAMES O'DONNELL

Classicist; Provost, Georgetown University; Author, The Ruin of the Roman Empire

Secrets are ignorance crafted by artifice. They represent knowledge made into a tool for advantage. When one breaks (that is, when somebody learns the secret who isn't supposed to), power and advantage can shift suddenly and disproportionately. We relish the moments of secret-breaking because we like the spectacle of sudden reversal — like an intercepted pass in football.

CLAY SHIRKY

Social & Technology Network Topology Researcher; Adjunct Professor, NYU Graduate School of Interactive Telecommunications Program (ITP); Author, Here Comes Everybody

"When does my right to privacy trump your need for security?" seems analogous to the question "What is fair use?", to which the answer is "Whatever activities don't get people convicted for violating fair use." Put another way, fair use is a legal defense rather than a recipe. ...

The complicated cases are where our deeply held beliefs clash. Should all diplomats have the right to all communications being classified as secret? Should all private individuals be asked, one at a time, how they feel about having their house photographed by Google?

I do not know the answer to this class of questions. You do not know the answer to this class of questions. This is not because you or I don't have strong opinions about them; it is because our opinions differ significantly from the opinions of our fellow citizens, and putting just one of us in charge would be bad for democracy.

So my answer to "When does my right to privacy trump your need for security?" is whenever various democratic processes say it does. If I publish something you wanted private and you can't successfully sue me, I was in the right, and when not, then not.

I consider Shirky's faith on the courts a bit naive.

Comments

Seems to me that Shirky was not naively believing that the law would get it right but rather was offering a answer as to how the question would be decided. It would be decided by a court ruling based on an arbitrary law. Being arbitrary, it might vary from place to place and time to time and the interested parties might not know the answer until the ruling came down. You place your bets and you takes your chances.

by A Guy Called LULU on Fri, 12/10/2010 - 9:12pm

That's not what he says. He says If courts support me, "I was in the right," not, "I was lucky."

by Donal on Fri, 12/10/2010 - 9:38pm

I think thr wor "if" is significant.

by A Guy Called LULU on Fri, 12/10/2010 - 9:53pm

Donal, I read your post as a series of questions and some answers by others that you have found online. They are important and topical questions because the answers are not obvious and yet getting the right answers, which affect us all, is very important. You do not answer the questions yourself which is fine. I would not expect anyone to give an answer that covers the various circumstances which beg the questions in the first place and that is the position I believe Shirky takes. I do expect that we will all get some insights that will inform our opinions as the conversation goes on. Most of us will end up thinking it is more complicated than we first thought.

Our disagreement is just on a small facet of your presentation. The assertion you make is that you believe that Shirky is naive in his belief that the courts will get it right. I still maintain that Shirky did not say that the courts will get it right and so did not demonstrate naivety in his answer.

Shirky poses various related questions and says that they all belong in a class. He then says that he does not know the answer and we do not know the answer, we just have our various opinions, and the only time we will get a legal definition of the answer in a particular case is when the question is taken to the courts.

I repeat, I do not see any confidence expressed by Shirky that the courts will necessarily get it right. He does not address that, he merely states how things are.

I see Shirkey's description of how the questions are answered as along the line of the different philosophical stances represented by the story about the three umpires calling pitches as strikes or balls. Umpire number one says, "I call them like I see them" Number two says,"I call them what they are". Number three says, "They aint nothin' 'til I call 'em".

Shirkey is saying that when it comes down to a legal decision of "When does my right to privacy trump your need for security?" and the related questions, that umpire number three's philosophy will be the one that carries the day.

My comments are usually either too long or too short. I tried to get away with one that was too short.

by A Guy Called LULU on Sat, 12/11/2010 - 11:28am

Well, if it is not naive, it is rather cynical.

by Donal on Sun, 12/12/2010 - 5:04pm

Fascinating stuff. It's late and this is a quick reaction but here's my take -- my privacy has been truly violated when you've intruded on my ability to imagine and think freely. My privacy has been unacceptably violated when you intrude on my ability to act freely in instances when my actions affect only other willing adults. I should only have to give up my personal rights to privacy and secrecy when it has become clear that my secrets have hurt unwilling others.

by Michael Maiello on Fri, 12/10/2010 - 10:21pm

<smiles> "Very Nice, Destor, I think you've got it."

by Donal on Sat, 12/11/2010 - 4:47am

But what if the only to make it clear that your secrets have hurt unwilling others is to invade your privacy? Isn't that the crux of the whole wiretapping, search and seizure, etc dilemma? I have to first prove that you are guilty in order to obtain the evidence that you are guilty. In the end we have to fall back on expecting authorities to operate on the basis of what is reasonable suspicion. And this is about as gray of an area that one can imagine.

by Elusive Trope on Sat, 12/11/2010 - 9:26am

As one who shuts and locks the bathroom door even when I'm alone in the house, I possibly value privacy more than is normal. There is a difference between privacy and secrecy, and, as one who shreds anything that even looks like I could be traced, I possibly muddy the waters in my own personal life, so I'm not the best one to pontificate on either privacy or secrecy. I don't see it as anywhere near black and white.

It may be that violating privacy/secrecy is okay as long as it's someone else who is being exposed. On the other hand, as one who respects the need for privacy/secrecy in others and tries very hard not to infringe. . .I possibly struggle with this more often than most.

I have to wonder, too, how those who preach for a more open society feel the need to do it behind pseudonyms.

An open society is an illusion and, to my mind, a foolish goal. We all have a need for privacy, of course, but we have an even greater need for secrecy. While our voyeuristic selves look at everything the Papparazzi and the tabloids throw our way, we don't want them finding out the things we wouldn't tell our mothers about. We all have secrets we wouldn't want exposed, and if we say we don't, we're lying.

by Ramona on Sat, 12/11/2010 - 9:24am

This is probably one of the biggest reason why many people who would become great politicians for the people don't go into politics.

by Elusive Trope on Sat, 12/11/2010 - 9:32am

Ramona:

I agree with you when you say: "We all have a need for privacy, of course ...." but I emphatically disagree when you say "but we have an even greater need for secrecy. "

Secrecy, Ramona, is by its nature, a one-way street that results -- because we are, as yet, imperfectly-evolved beings -- in the manipulation of others without their informed consent. He or she who knows more and who chooses to willfully withhold that knowledge from others -- whether in government, or within community or personal relationships -- gains an unjust advantage.

Secrecy -- until we evolve further -- is, in essence, a weapon.

by wws on Sat, 12/11/2010 - 11:33am

"Everything secret degenerates, even the administration of justice; nothing is safe that does not show how it can bear discussion and publicity." ---Lord Acton

Hey, wws; nice to see you!

by we are stardust on Sat, 12/11/2010 - 11:56am

While I agree that people with bad intent can use secrecy to manipulate others, it is also true that knowledge can be a weapon as well. That is why we believe in an individual right to keep their physical and mental medical records secret. I sure don't want to have to list my medical history on my job application, even though the business owner might claim he or she has the right to know just who it is they are hiring. And local and global law enforcement would become completely ineffective if criminals from insider traders to criminal networks like the one ran by Khan were able to know what specific individuals were under surveillance and targets of investigations. I suppose one can say that secrecy can be "weapon for good" against such things, for example, as those who would discriminate against those with HIV or a history of depression, or those who would rob and kill and otherwise create suffering among the innocents.

by Elusive Trope on Sat, 12/11/2010 - 11:58am

wws, How exactly do we function in an "open society"? How open is open? Is anything closed to us at all? If not, how do we avoid that same openness from crossing over into our personal lives? Will we all be living in glass houses?

I guess I don't see the word "secrecy" in the same vein as you do. It can be an instrument for evil, but that doesn't mean it always is. I can't imagine a society where all secrets are exposed. I'm still trying to figure out how that would work to our benefit.

by Ramona on Sat, 12/11/2010 - 1:29pm

Ramona: Your question of what defines an "open society" is one well worth trying to define -- by loose consensus, if possible.

The first clarification we need is a defining difference between "privacy" (the preservation of which in general terms would be regarded as a positive) and "secrecy" (which, historically, more often than not, has been and is, imo, a negative).

The second thing we might consider is that if there is invariably to be error in one direction or another -- instances in which the ideal boundary we establish between privacy and secrecy is breeched -- which is the lesser offense for the common good?

The third, if tangential issue we might consider is whether or not personal embarrassment is a price worth paying if it precludes the evil that manipulative secrecy spawns.

I've been rereading LeCarre recently -- his more recent books first and then working my way back to his first efforts. My intent was escapist -- just to be temporarily enthralled and entertained by an accomplished wordsmith whose world was and is so ostensibly removed from my own. But what I have discovered, instead, is how prescient LeCarre has been, in not only providing early warnings of various kinds of global crises, but also in explicating their cost, not only in economic or political terms, but also in terms of morality versus amorality in ways that affect us all, as individuals.

One paragraph literally leapt off the page (sadly, I'm paraphrasing, having already returned the book to the library):

"The insidious quality of evil is that it is so tiring; it is relentless in its predatory agenda and thereby ultimately enervates its targets, leaving us, finally, too exhausted to effectively counter and ultimately prevail. Evil has an unfair advantage: it acknowledges no rules of engagement, it says one thing and does another. Secrecy its greatest weapon."

You may have other questions than mine in trying to come up with a workable consensus. Any questions are fair enough. What isn't fair, imo, is forcing a society, a community or any individual to make choices with limited information.

by wws on Sat, 12/11/2010 - 3:05pm

We feel the "right" to do just about anything we want to do in the privacy of our homes. If we feel like doing something we want to keep private we close our curtains. If we leave them opened and someone walking down the street sees what we are doing we can expect them to talk about it and not expect them to be legally sanctioned for doing so. If they enter our property to get a closer look, or to peek through the shades, then that is a different matter.

If you put heavy curtains over all your windows but at night there are brilliant shafts of light passing through any opening and someone notes that you are running five hundred dollar electric bills and the neighbors smell a sweet pungent odor, they might feel justified, and maybe obligated, to tell the police that they suspect a grow house. The police will be able to get a warrant on the grounds of evidence that you are secretly doing something illegal and suddenly you have lost that right to privacy even if you are growing orchards. The judge will have temporarily taken away your right to privacy whether you have actually forfeited it by your own actions or not.

If you have reason to believe that someone is abusing a child in their home, and notifying the authorities has done no good, I think you have the right and the obligation to break the law and sneak onto their property and peek through their windows so as to get evidence and force the authorities to do right. If they don't you should call the newspaper and try to get them ito expose the authorities.

If you have access to information that shows that your government is secretly hiding the fact that it is lying to its own people to cover up the fact that it is doing things which which are illegal and often completely unconscionable, then the honorable thing to do is reveal what you know. Bradley Manning was arrested 198 days ago and is in solitary confinement because he supposedly did what I think is an honorable thing. This spouting off on the internet is pretty easy, especially doing so under a pseudonym as I do so as to maintain a niche of privacy for my rants.

by A Guy Called LULU on Sat, 12/11/2010 - 2:12pm

In addition to the themes of secrecy and privacy, there is another connection of the 451 Family to internet social media that merits attention; the element of interactivity.

In the story, Mildred/Linda does not merely want to be passively entertained. She seeks engagement and active participation in the scene. The desire for the fourth wall is a desire for immersion. She blames the absence of that wall for the dissatisfaction with the experience.

On a number of levels, Fahrenheit 451 is a conversation with Orwell's 1984. There is agreement and debate. While agreeing that control of messages is central to the method of controlling populations, the element of interactivity replaces the division of labor necessary to have watchers watching the watchers.There is an economy of effort involved with development of a virtual world.

In the context of their marriage, Guy and Mildred do not need each other. They also do not need privacy as a couple because there is no intimacy. The love between two people is a secret place. The privacy comes not from some barrier that is set in place but from not needing to borrow something from others. John Donne expressed it well:

Mildred and Guy both want experiences they don't provide each other. By going separate ways it can't be said that either one changes the structure of power in any way. One remains inside and the other outside. I suppose one question that could be asked about the interactivity of the web is whether it is proof paid to the virtual world presented by Baudrillard or is a way to help preserve something Outside of the structure the virtual world replicates.

by moat on Sat, 12/11/2010 - 3:33pm

You might enjoy a gander at what Umberto Eco thinks:

http://www.presseurop.eu/en/content/article/414871-not-such-wicked-leaks

by artappraiser on Sat, 12/11/2010 - 6:52pm