MURDER, POLITICS, AND THE END OF THE JAZZ AGE

by Michael Wolraich

“Let yourself be drawn by the stronger pull of that which you truly love.”

-- Rumi

Going back over some bookmarked articles, given my latest focus, a couple of articles caught my attention. First there was the following passage from The Guardian article on Czech photographer Josef Koudelka::

After the Prague pictures established his reputation - or at least that of an "anonymous Czech photographer" - Koudelka left the country on a three-month exit visa to photograph Gypsies, a project he'd begun in 1966. Failing to return home at the end of that period, he became stateless, a status he craved the way others yearn for money or fame. He felt at home in exile. All he needed, he insisted, was a good night's sleep, plenty of film, and time. Everything else was a seductive distraction: the less he had, the less there was to miss. "I needed to know that nothing was waiting for me anywhere," he has said. "That the place I was supposed to be was the place where I was at that moment, and that when there was nothing more to photograph there, then it was time to leave for another place."

I think it safe to assume that most people tend to identify with those who crave wealth and fame, as opposed to those who crave something similar to Koudelka. At the same time, for some of these dreamers of wealth and fame, there is a romanticization of the vagabond lifestyle. (Probably one of the significant moments in my life was when one of my teachers in high school handed me On the Road and told me that I should read it.) I reminded of a comment made by ocean-kat on a recent blog of mine:

For about 15 years I worked as a painter/handyman for very rich very liberal lawyers and doctors. I'd come into usually Philadelphia for 2 months and in a van I lived in, parked and lived in their driveway, worked constantly 12 to 14 hour days, make a fat wad of money and left to travel. These rich liberals treated me like a long lost brother and romanticized my life. I didn't just shower and shit in these rich people's bathroom, they invited me to supper often and made me special suppers occasionally.

I'm educated but I was never able to make it work for me and find a place among the wealthy elite in society. My life style has its rewards but its also been a struggle, not at all like these people imagined.

The grass is always greener on the other side of the fence, especially when one is feeling that the current side of the fence isn't so fulfilling. Everyone at some point go through a version of the alcoholic train of thought that concludes 'if only I was living in a different place (or had a different job, was in a relationship, wasn't in a relationship, etc), then life would be good and fall perfectly into place.

“Every living organism is fulfilled when it follows the right path for its own nature.”

-- Marcus Aurelius, Meditations

At the core of this kind of train of thought is the belief that it is forces outside of oneself which are keeping one from finding fulfillment. A conspiracy of the universe to thwart one's happiness.

This is not to say the world has something to say about which path one finds oneself going down. The other article that caught my attention was an interview in The Guardian with Czech author Ivan Klima, which quotes him as saying:

"Anyone who has been through a concentration camp as a child," he once wrote, "who has been completely dependent on an external power which can at any moment come in and beat or kill him and everyone around him - probably moves through life at least a bit differently from people who have been spared such an education. That life can be snapped like a piece of string - that was my daily lesson as a child."

The "education" we receive from life has a lot to do with just what life we handed, the path we are given. Even then, our previous education will influence how we respond to most current educational lesson. One event that Klima and Koudelka share was the Prague Spring in 1968. It was an event that altered both of their lives, just as they had a significant role in influencing the event itself.

But while Koudelka became stateless, Klima returned to his home state:

If 1989 was the best of times, the worst of times, Klima says, was 1970. When the Russian tanks had rolled into Prague in August 1968, Klima was in London, en route to a teaching fellowship in Michigan. Shaken by the news, he carried on to the States with his family, and when the teaching stint came to an end a year later he was faced with the toughest decision of his life. Should he stay in exile in America, as many Czech dissidents did, or should he take his family home?

"Everyone said: don't go back, they will send you to Siberia," Klima recalls. "But I just felt there was no sense for me as a writer to stay abroad, missing not only the language but the connection with the people you best understand. I could admire Americans but their problems were not my problems."

Klima returned in March 1970 at the height of the Soviet-backed purges. "It was very frosty," Klima recalls. "They banned everyone who had been involved in the Prague spring; 400,000 people lost their jobs, nearly all highly skilled people, teachers, lecturers, everyone from radio, TV, trade unionists." Klima was blacklisted as a writer, and prevented from working except in menial jobs. He had his passport removed, his driving licence taken away, his phone cut off. He was threatened with prison if his books were published abroad and a law was passed which allowed the state to take foreign royalties deposited in bank accounts.

I would assert that the vast majority of those people who crave wealth and fame the way Koudelka craved the life of the exile also see a fulfillment of that craving as bringing happiness. And not just a brief transitory happiness, but life-long happiness.

Yet following the heart does not necessarily bring happiness. It is likely to bring pain and suffering. Life is hard. If one believes one has found the easy path to the infamous catbird seat, he or she is almost assuredly in some delusional frame of mind.

Geoff Dyer writes of Koudelka:

In 1971, he joined the photo agency Magnum, which gave him the advantage when he was passing through of bedding down in the Paris office. The apparent meagreness of Koudelka's hobo existence was itself a kind of wealth. You can see that in some of his best-known pictures, from Slovakia and Romania, of people who, while possessing very little, are experiencing life and all its dreadfulness in grim abundance. In Koudelka's view, the glass is never half-full or half-empty; it is always overbrimming - even if what it is overbrimming with is tears.

The tragedy and carnage of an event like the Boston Marathon bombings lead us to ask why someone like the brothers would do what they did. Part of the confusion for some comes from the fact that the brothers were enjoying the good life that U.S. and other developed countries offer. As if it was as simple as that.

Many moons ago I head some discussing poverty (I believe on the Charlie Rose show) make the comment that while it was more physiologically difficult to be poor in the Philippines than compared to the U.S., it was more psychologically difficult in the U.S. than compared to the Philippines. The reason being in the Philippines, just about everyone is as dirt poor as you, while in the U.S. the poor are surrounded by evidence of those who are quite wealthy. It is a lot easier not to have anything, to hear one's stomach growl from hunger when one doesn't have to look through the window and see others enjoying a meal that costs more than one makes in a year.

One last article I had bookmarked was from the New York Times regarding Spalding Gray. In one of his journals, Gray wrote on March 7, 1972:

I realize that the jig is up. This lazy in-between: I’ve really got to come to terms with Liz, me, the work — who I am and what in hell am I doing with my life — without comparisons. I feel as though I’m reaching a large crisis point in my life . . . I can’t turn away from it.

It is that "without comparison" which is critical for the discussion here. How much time do we spend comparing the path we have found ourselves on with the path others are walking. Or more accurately, comparing our path with our perceptions of the paths of others. At times it seems as if this compulsion to compare is genetically encoded in us.

And too often, we find our path coming up lacking in the final analysis of paths. We listen to others' criteria as to what constitutes the true path, the shining path. We would do ourselves a favor if we at least practiced judging our path without comparison. We might find a joy (which is not the same as happiness) even when our path is overbrimming with tears. A joy that does not lead us down a path which leads to creating more carnage and suffering in the world. There is plenty of that already.

“I exist as I am, that is enough.”

-- Walt Whitman

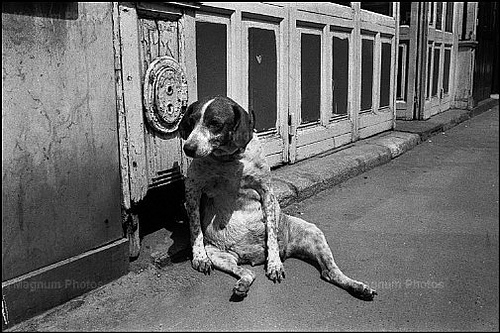

All photographs in this blog by Josef Koudelka

Comments

The "compulsion to compare" must be genetically encoded in us. It is the waving flag in the semaphore of our shared experience.

The crisis point Spalding Grey talks about demonstrates how how the personal is sometimes not politics at all. There is a show only one person gets to see.

I think the act of comparing is what Kafka's Metamorphosis is about. One can lose the battle with all the things that make you this and that. You can't blame anyone for avoiding the fight at all cost. Gregor Samsa fought it but lost. If Gregor had managed to have gotten out of his apartment that day, the result would have been different. Either he didn't put up enough of a fight or too many odds were set against him. At the very least, Kafka is underscoring a certain kind of vulnerability, different from other kinds: A comparison, if you will.

Maybe our problem is not the act of comparison itself but what we place side by side.

by moat on Sun, 05/19/2013 - 6:41pm