MURDER, POLITICS, AND THE END OF THE JAZZ AGE

by Michael Wolraich

Fascinating longish read to take one's mind off of coronavirus, discovered @ Arts & Letters Daily with the intro. “The secret of black intellectuals is that we have other interests.” Darryl Pinckney, Margo Jefferson, and others discuss race and intellectual life... more »

Since it says "Part I", I presume there will eventually be more.

Comments

I still remember a comment from Alejo Carpentier, a writer and composer who'd gone into exile several times, on how he could work and somehow endorse Castro's repressive Cuba, effectively "I am concerned with time, with centuries, not these temporary political matters." Perhaps not entirely honestly, but still, is everyone in society required to champion the exact same things, morals, causes, protests, world views...? Is that not repression in itself? Where's Whitman's "I contain multitudes", for the individual, for the class, for the group, for the nation's and cultures? Why does "diversity" get dragged down by this suburban "conformity"?

by PeraclesPlease on Thu, 05/07/2020 - 3:23pm

Finished the first section. Interesting read.

Poor Coates takes it the chin as do current students walking around with scowls due to anger about racial inequality. The panelists note the progress made in the last 50 years. It is noteworthy that the panelists seem to ignore the dramatic decrease in crime since the 90s. This decrease occurred despite the popularity of rap music. Teen pregnancies have also decreased. Unwed mothers remain with us despite's the plunge in crime. This overlooking of new data by Orlando Patterson was pointed out in a New Yorker article.

https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2015/02/09/dont-like

It would be nice to have more discussions between the culturalists and the structuralists.

Get to the rest of the article over the weekend.

by rmrd0000 on Fri, 05/08/2020 - 10:35am

While the peak in homicides and crime in general was a landmark achievement, it's nearly 30 years on. What's the next act? Of course having a decent government, no economic crash, no pandemic are easential to a new stage.

by PeraclesPlease on Fri, 05/08/2020 - 11:03am

It will be interesting to see what happens to violent crime. If it continues a downward trend despite severe economic hardship, pandemic deaths impacting minority communities, and the Trump government , we will all be searching for answers.

by rmrd0000 on Fri, 05/08/2020 - 11:42am

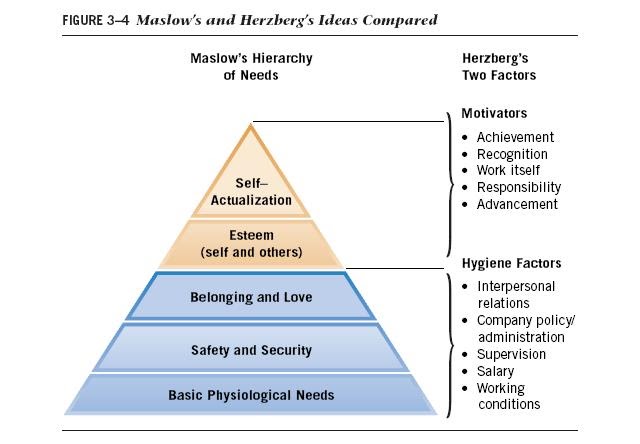

Crime falls under hygiene factors.

Need motivators in the next stage.

by PeraclesPlease on Fri, 05/08/2020 - 12:22pm

Humans are biological oscillators. Academicians are sometimes slow to adapt to change. As we watch the response to the coronavirus and see new phenomena occurring with asymptomatic hypoxia, blood clotting disorders, strokes, right heart failure, abnormal heart vessels in children, etc, we see the limitations of our perceptions. Ventilator therapy has changed. The pathophysiology is not understood. Researchers are truly observers.

I view the same thing happening in the social sciences. There is a box (or triangle) and we try to force observations to fit the triangle. The homicide rate decreased despite hardcore rap, unwed mothers, poverty, etc. Models do not explain what we see. We then observe and record results rather than force what we see into a figure previously created. We may need more than one dimension.

The panelists are confused by why they see scowls on campus. This tells us that their models are crap.

by rmrd0000 on Fri, 05/08/2020 - 1:03pm

Wow, are you dismissing the 2 most influential organizational psychologists of the last century because... what exactly? You don't like triangles? (a pyramid, technically - and that's Maslow - Herzberg's the two-factor theory.

(Maslow introduced positive aspects into Psychology - not just a bag of problems, but positive aspects too. - try it sometime)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Abraham_Maslow#Maslow's_contributions

by PeraclesPlease on Fri, 05/08/2020 - 1:17pm

Doesn't seem to be helping the panelists understand why their students are pissed.

by rmrd0000 on Fri, 05/08/2020 - 2:04pm

Maybe they should read. Or even take some of their schools' Organization and Management classes.

by PeraclesPlease on Fri, 05/08/2020 - 4:26pm

The models do not explain the decrease in homicides.

Edit to add:

The are so focused on culture and Coates, they seem not to notice that things have changed. They have a blind spot.

by rmrd0000 on Fri, 05/08/2020 - 4:44pm

What are they not seeing?

Edit: I am not asking because I know the answer.

by moat on Fri, 05/08/2020 - 6:33pm

When you are young, you are not thankful that things are better than they were 50 years ago. Young people look at their status as it exists today, You see armed whites wanting businesses to reopen. You see the data the the groups most at risk are marginalized groups. You actually hear white politicians telling you that Big Mama should be sacrificed. Trump is President and feeding red meat to majority white rallies. You are pissed.

If you listen closely to the panel, you hear older people telling you to let things go. That is not going to happen. McWhorter tells you that the police are not a big threat. If you personally have not have had a bad interaction with police, you know or have heard of someone who has. You turn on your television or read stories on your iPad about a black man shot by Dallas police while in his own apartment. You see video of a black man shot three times while jogging in Georgia. In both cases, local law enforcement made no arrests. It took public pressure to get both cases to trial. When the white Dallas police officer is convicted, you see the black judge hug the officer. No hugs for the murdered man's family. You feel that McWhorter is a fool. That is why several of the panelists say their students think that the panelists are out of touch.

Orlando Patterson correctly says that most whites have no problem accepting blacks, but he also acknowledges that there are about 20% of whites who are racists. He says that they will not change. He tells his black students to "get over it". He then will chastise black students for the cultural error of listening to rap music. McWhorter and Williams follow suit. Blacks have to change, the racist whites will always be with us.

The students also know that there are more men in their age group in college than in jail. They are aware of the decreasing homicide rates. They realize the homicide rate is too high, but damn, if you want students to be thankful that conditions are better because whites have gotten better, at least point out that in most places the black homicide rate and teen pregnancy rates decreased.

(Edited to correct typos)

by rmrd0000 on Fri, 05/08/2020 - 8:58pm

Thank you for the thoughtful response.

by moat on Fri, 05/08/2020 - 8:14pm

You're welcome.

by rmrd0000 on Fri, 05/08/2020 - 8:54pm

Very interesting discussion. I got half way through and realized I was going too fast and will have to start over.

The observations made by the audience members are some of the best parts.

by moat on Fri, 05/08/2020 - 3:36pm