MURDER, POLITICS, AND THE END OF THE JAZZ AGE

by Michael Wolraich

Order today at Barnes & Noble / Amazon / Books-A-Million / Bookshop

|

MURDER, POLITICS, AND THE END OF THE JAZZ AGE by Michael Wolraich Order today at Barnes & Noble / Amazon / Books-A-Million / Bookshop |

The Great Stagnation: How America Ate All The Low-Hanging Fruit of Modern History, Got Sick, and Will (Eventually) Feel Better by Tyler Cowen

The Great Stagnation, a short yet ambitious e-book by economist Tyler Cowen, has been generating a lot of buzz lately. It has been recommended by Matthew Yglesias (ThinkProgress), Ezra Klein (Washington Post), Tim Harford (Financial Times), and Nick Schulz (Forbes), to name a few.

I bought the book on the suggestion of EmmaZahn here at dagblog. I found it to be clear, original, and so engrossing that I missed my subway stop. But I did not ultimately find it persuasive.

In the book, Cowen argues that America's spectacular growth of the past 200 years has been driven by the consumption of "low-hanging fruit" which we have now exhausted. In particular, he cites cheap land, advances in education, and technological innovation. He argues that since we can no longer rely on these drivers, our economy will stagnate for the foreseeable future.

But you don't have to be an economist to see that the evidence Cowen relies on to bolster his low-hanging fruit theory has been derived from some aggressive cherry picking.

I'll focus on the technological innovation element, since that's what Cowen spends most of his time discussing. To demonstrate that technological growth is slowing, Cowen cites an article by physicist Jonathan Huebner which argues that per capita innovation peaked in the late 19th century and has now dropped to the level of the Dark Ages:

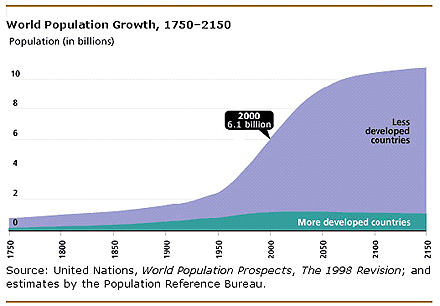

The key phrase is per capita, however. The chief cause of this alarming drop is not a decline in the rate of innovation but rather the exponential growth of human population. From an economic point of view, the per capita number is indeed significant, but it's not particularly relevant to Cowen's point regarding American stagnation. That's because almost all this technological innovation has come from the industrialized world, where population growth is far slower.

I don't have the data to redraw Huebner's chart in terms of American-specific innovation and population, but you would certainly see a far less dramatic curve.

Beyond this chart, most of Cowen's evidence is anecdotal. He observes that the technological changes of previous generations had a far greater effect on peoples' lives. The advent of the automobile, the telephone, and refrigeration changed the world. By contrast, the innovations of the past few decades, such as more efficient cars and refrigerators that make ice cubes, have not been revolutionary.

Except, one might think, the Internet, which Cowen promises to address in Chapter 3. In Chapter 3, he acknowledges that the Internet has changed our lives, mainly because it's so much fun. In fact, he uses the word "fun" in the context of Web surfing seven times. (I found myself thinking, "OK, I get it. The Web is fun.")

Nonetheless, Cowen argues that the real economic impact of the Internet has been relatively small because so much of it is free and automated. He observes that Google, Facebook, eBay, and Twitter collectively employ fewer than 40,000 people.

Have you spotted the cherry picking yet? Google, Facebook, eBay, and Twitter are rich, successful companies, but they are like pretty blossoms on the tree of the computer revolution. The technology sector employs 5.8 million people in the U.S., and that doesn't include all the workers who rely on computer and internet technology, which is almost everyone. In the past 30 years, the computer and the internet have revolutionized every industry in the nation, from manufacturing to finance to government to publishing to Cowen's own field of economics.

Here's one tidbit from the book that nicely illustrates Cowen's technology myopia. At one point, he argues that the growth of large corporations and centralized governments was made possible by the innovation of paper file systems in the late 1800s. Simply put, large-scale bureaucracies require the ability to track people and goods.

So what has been the greatest advance in file system technology in 100 years? The computer database. In the 1980s and 1990s, database and network technology vastly increased the efficiency and scale of modern bureaucracies. But Cowen doesn't even mention it.

Indeed, Cowen only uses the word "computer" five times (two less than "fun") and only in the context of home computing. Think about that. He wrote an electronic book full of computer-gathered statistics about the economic impact of technology without so much as broaching the subject of computers in the workplace.

Towards the end of the book, Cowen diagnoses the failure of economists to appreciate the scale of the Great Stagnation, arguing that the contagious optimism produced by a boom economy led them to ignore the contrary data. He even confesses that he himself failed to anticipate the financial crisis because he was caught up in the optimism.

But just as boom times lead even hard-nosed economists to wear rose-colored glasses, economic busts lead many of the same economists to interpret data in an overly pessimistic way. Despite the many original ideas presented in The Great Stagnation, it is nonetheless a classic recession-driven fit of gloominess. Cowen is still caught up in the social hysteria; it's just that the hysteria is now going the other way.

Comments

Still have not read it myself and nor its review by that got the most buzz by Steve Waldman which seems almost as long and requires more focus than I have been able to muster.

From some reviews and Tyler's own statements, I thought he was writing about a stagnation in the discoveries and inventions on which technological changes are built and not the changes themselves. I must have misread.

Anyway, I cannot agree with Tyler's conclusion because what I think fuels innovation most is shared knowledge and not just what is shared by formal education. The internet(s) and a for-all-practical- purposes universal language enable us ordinary humans to share knowledge at a truly phenomenal rate. Anyone who thinks they can forecast what may develop out of this for good or evil is kidding themselves.

Oh, and thanks for the shout-out but the link does not work. :)

by EmmaZahn on Mon, 02/21/2011 - 8:12pm

The link is fixed. Tyler is talking about the innovations, but he measures their significance by the changes that result. For instance, the automobile is so significant not because of the scale of the innovation but because of its impact on peoples' lives.

Thanks for the recommendation. It was well worth the read, despite my criticism of the methodology.

by Michael Wolraich on Mon, 02/21/2011 - 8:25pm

Shorter: You're right, Genghis.

Longer: People should go read some Carlota Perez.

http://www.carlotaperez.org/lecturesandvideos.html

She's taught at Cambridge, Sussex and in the US, and has put tonnes of articles, powerpoints, pdf's, videos, up on her site. It kicks this sort of pseudo-historical nonsense from people like Cowen to bits. She looks at long waves of technological change, at what stages are led by finance capital, when finances bubbles, how it rolls out into mass employment and a sustained uplift, etc.

Her most recent book was: Technological Revolutions and Financial Capital: The Dynamics of Bubbles and Golden Ages.

Full disclosure: I know CP, and have worked with her some - but she's out of my league smarts-wise, the ideas are all hers, and I'll let her work speak for itself. But I find her stuff provides a useful framework to help understand where we are, why, and what can come next.

by quinn esq on Mon, 02/21/2011 - 11:53pm

Thanks, Q. Looks intriguing. I'll check her stuff out.

by Michael Wolraich on Tue, 02/22/2011 - 9:28am

Genghis,

Your criticisms are well argued, and reveal the vulnerability of Cowen's exposition and it is true that to be gloomy is the fashion now, but at the same time, it is Cowen's principal insight, the idea of America's "low hanging fruit" that is important... The idea is valid. The USA has had an incredible free ride from colonial times till recently and times have changed. I think that is why the book is doing well. "In our hearts we know he's right", sort of thing. In short he's right, but he has been sloppy in developing his argument. If you had been his editor the book would have been better.

Adding to this, I would say that after hundreds of years, the USA is beginning to face problems and limitations that other less fortunate countries have always faced and that this will be a wrenching readjustment.

by David Seaton on Tue, 02/22/2011 - 3:24am

What readjustment? America is in a unique position it can be an island.

Stop exporting our jobs, quit importing foreign goods.

Our United States is a blessed Nation, with bountiful resources.....The low hanging fruit is still there,

The problem IMHO is; the world's industrialists view America as a colony, to be exploited for it's natural resources.........

The industrialist’s attitude towards Americans "To hell with the people living on the land”

The industialists have it all figured out, bad treaties have always worked before"

Independence Day .....President Thomas Whitmore: “What do you want us to do?”

Captured Alien: “Die. Die”

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2Rw5MosKRm4

American people: What do you want us to do?

Industrialist, banker class: Die. Die.

The industrialists only want our resources, our land, our timber, our minerals; your blood.

John Q public has a new name; Ben Dover

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wxiMrvDbq3s

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1yuc4BI5NWU

by Resistance on Tue, 02/22/2011 - 5:04am

Well, to become an "island" would be a major "readjustment", that's for sure. I don't think that would work and to try it would probably lead to WWIII and, as Einstein said, WWIV will be fought with sticks and stones. The world is interconnected whether we like it or not, the question is how to live in peace, with justice for all and that means liberty, equality and fraternity around the globe. Tall order, nu?

by David Seaton on Tue, 02/22/2011 - 5:54am

The idea is interesting, but that does not make it valid. Cowen himself argues that you need to focus on the data because those gut feelings are so often wrong (as our last president so amply demonstrated).

There's a reason that gloom is in fashion now. Our guts (or hearts or whatever) are telling us that the sky is falling, just as they told us that prosperity would never end during the boom.

by Michael Wolraich on Tue, 02/22/2011 - 9:41am

The idea that America was singularly blessed by fortune was driven into me as a child and I was repeatedly reminded it of by Europeans and Japanese who had survived WWII.

I come from a family with pioneer roots going back to the 17th century, who indentured themselves in order to get from the British isles to the Virginia colony, who worked homesteads and sold them and with the profits moved farther west and homesteaded bigger homesteads and sold them until they finally arrived to homestead in the "promised land", Iowa, in the 1840s. America was the only place where a European yeoman could get land of his own... for free, and near the Mississippi, where all the corn could be sold at a good price to be shipped to New Orleans on rafts and then sold to Europe.

Of course America is about "low hanging fruit". Ask any Iowa Indian

by David Seaton on Tue, 02/22/2011 - 10:52am

David, why so intellectually lazy? A book selling well in the US BECAUSE it's intellectually valid? Right after noting, "to be gloomy is the fashion now?" Gee, looks like you had to give up one hobbyhorse (Americans all about buying trendy stuff) to hang onto an old fave (David taking the gloomy view of the US.)

Sounds to me like you can't be bothered to read any explanations deeper than "Urrrrrm, we runded outta the low-hangin' fruit, Ma. Looks like wer doomed. Best we go crawl inta tha root celler."

How about I explain things on your end, a la Seaton: "The Spanish have always been lazy. They're bred for laziness, ever since they colonized the Americas. Recently, they managed to make a nice living off money coming in from rich (harder-working) Northern Europeans who came to build houses in the sun. Naturally though, the lazy Spanish got carried away with their greed, everyone thought it would make their fortune, and now... they've lost it all. Oh well."

Thought, Seaton-style.

by quinn esq on Tue, 02/22/2011 - 3:19pm

"The Great Stagnation" sounds like an excellent counterpoint to Kurzweil's "The Singularity is Near"—and vice-versa. I don't think either author has all of the details correct, but personally, I'd put more money on Kurzweil's vision than Cowen's, but maybe that's just because I'm bullish on technology.

by Verified Atheist on Tue, 02/22/2011 - 7:47am

I haven't read the book but I think your blog points out that the economy is like the weather. The experts can talk very intelligently about the factors involved, explain why something did happen the way that it happened, but when it comes to predicting how something will unfold in the near future (let alone years down the road) they are basically making informed guesses due to the vast number of variables that come into play and interact with one another in quick period of time. Economists seem to me to be one of those groups of people who can't come to terms with the reality of "chaos" in the system (such as "sensitive depedence on initial conditions") and keep trying to impose an order that isn't there. In part, they seem to keep trying to take the human factor out of the equation.

by Elusive Trope on Tue, 02/22/2011 - 9:35am

So america's spectacular growth has been driven by the consumption of "low-hanging fruit" which is exhausted, eh? Guess he never heard of that fellow Darwin. Fruit trees procreate by dispersing its seeds. Wouldn't make much sense if the seed pods were too high where the intended dispersal agents couldn't access them. So nature does her thing and ensures the fruits of her labor are within the reach of those distribution agents...she makes more available at the lower limbs so as to speed up the dispersal process.

And america wasn't at the forefront of the industrial age either...England was the mother of those inventions. However, america took the concepts and ran like the wind and surpassed the English at their own game.

It's not so much the concept of original thought as it is the ability to transform a thought into a product where america is great. So as long there is someone who has an idea, america can make it come true.

by Beetlejuice on Tue, 02/22/2011 - 10:26am

Ideas are not enough; the industrialists will take the produce from the idea and propagate the seeds of the idea onto foreign soil.

If you try to have a homegrown crop, a cheaper FOREIGN labor force will undermine it. Your idea will make others rich.

A foreign interest is not interested in Americas prosperty, GET IT

The new industrial concept; the same as the old industrial concept, Slavery makes the industrialist more profits...

The idea ....Labor is a commodity to be exploited.

The plan is in place to acommodate the "exploitation idea"

America doesn't need to accept being enslaved or made to compete against slave made products.

Why are we making trade agreements with dictators? Making trade agreements with partners who have no moral values as regards human rights or work conditions or work safety or environmental considerations.

Of course the industrialist propaganda machine convinces some Americans, to sell out their self-interest, some stupid Americans convinced that purchasing slave goods helps the slaves become middle class citizens.

Stupid Americans wondering where are the jobs, where is the safety net, where is the retirement, the healthcare financing, to come from to support AMERICANS?

This One World happy talk, is BS.

One world of slavery is the plan, resist it and your country will be brought to it's knees, the better days will never come, you will submit or be economically destroyed.

With no tax base, because the industrialists has relocated manufacturing overseas; whose supposed to pay the bill? The unemployed; the Wisconsin State worker, how about the homeowner upside down on his mortgage, you think they can pay more taxes?

The economic system of America destroyed, for the sole pupose of enslaving the American worker. CAN'T YOU SEE IT?

Who took your homes, your healthcare and retirement? Did you just give it away or was it a plan to take it away?

Americans will either become slaves or be beaten into submission in order to compete in a slave commodity world.

Stop the export of jobs and the importation of goods, for the sole purpose of benefiting the merchants

How much longer must America suffer, because stupid Americans have rejected the instruments of defending against those who would take our freedom and enslave us?

Tariffs and duties as a revenue source, to be used in the protection and support of AMERICAN workers.

by Resistance on Tue, 02/22/2011 - 1:10pm

"I fear all we have done is to awaken a sleeping giant and fill him with a terrible resolve."

Japanese Admiral Yamamoto

by Beetlejuice on Tue, 02/22/2011 - 10:00pm

How about this. We have at least a dozen major industries that I know of, in the energy and environmental "sector," where costs are falling by 10%-30% annually. Take wind and solar and the lithium-ion batteries needed by plug-in and electric vehicles. Now, if you run that film a decade, and let those costs continue to fall, then you will have, by the next decade, cars.... that have no emissions... that cost the same as cars today... and electricity... that has no emissions... and costs the same as electricity today. In some parts of the world, this is ALREADY the case. I looked at wind projects today that cost 6-7 cents/kwh on the Prairies. That means, the rough equivalent of 25 CENTS per gallon gasoline. Which can be put in a new Toyota Plug-In Prius as of next year - 2012 - and which will happily carry Winnipeggers back and forth to work, and have a sticker price of UNDER $30,000.

Now, buddy Cowen doesn't seem to think this is revolutionary enough I guess. And compared to the introduction of the automobile, or the electrification of the countryside, it isn't. But is it absolutely necessary, incredibly engaging, cost saving, ass saving and job-creating? Yes.

The great BIG monstrous innovation, the one that will be looked back upon in 1000 years though, is the Internet. I almost find it embarrassing when someone writes stuff like Cowen, and fails to recognize that we've just laid the basis for changes in every bot of human knowledge, where we've found ways to wire ourselves together, where we're developing new senses, where we're wiring the human genome and sensorium together with the world in an incredible new way - and we're ONLY AT THE 5 MINUTE MARK IN THIS REVOLUTION... but he thinks TV and dishwashers or somesuch is a bigger breakthrough.

The word "computer" 5 times? I think that nails him in a sentence Genghis.

by quinn esq on Tue, 02/22/2011 - 12:19pm

We'll have to lower the costs of cars and electricity, because who'll be able to afford it otherwise.

The cars and the batteries will be produced, where labor is cheaper.

I guess home values have a ways to go before they hit bottom and can become affordable for the new slave class.

The States will have to lower expected tax revenues that are based upon lower property values.

All workers including Wisconsin State workers will need cheaper electricity and cars, I suspect with lower electricity costs and cheaper transportation, the Government can then cut the overhead costs of entitlements. Everything else will be cheaper, even labor costs.

Are you willing to compete against slave wages, if not, you won't need a $30,000.00 car or will you be able to afford one, to go to work, there won't be a job for you to go to?

Maybe the cheaper electricity will allow the customer to afford, to turn the furnace on, when the bitter cold winter comes?

I don't see Utopia on the horizon, I see American workers in despair, unable to compete in a slave driven labor pool.

A $30,000.00 dollar car driven by a chauffer works for the wealthy industrialist?

by Resistance on Tue, 02/22/2011 - 1:42pm

I think that is where things are going. Something like a third world country, Brazil if we are lucky, Nigeria if we aren't.

by David Seaton on Tue, 02/22/2011 - 2:10pm

Trenchant.

by quinn esq on Tue, 02/22/2011 - 3:20pm

Found the flaw in your argument, quinn. Happy Winnipeggers? I don't think so.

by acanuck on Tue, 02/22/2011 - 3:43pm

An objection regarding this point of yours:

Huebner explicitly addresses this point in the article you and Cowen cite:

It's a less dramatic falloff, but not inexistent.

Not that I disagree with your overall point, but I don't think your formal quantitative critique is valid.

What I find strange about the book is how Cowen seems to be desperately avoiding the real problem. He identifies the phenomenon of stagnation by noting the flattening median household income trend over the last 40 years, while ignoring the fact that economic growth - i.e. gdp - has continued pretty much unabated over that period. So, in short, there is no economic stagnation, there is only an upward distribution of the gains from economic growth such that ordinary families have faced income stagnation. And THAT phenomenon is something that a conservative like Cowen really does not want to face, because of the uncomfortable conclusions about regulatory and tax reform it might involve.

And it isn't just Cowen, it's like the whole economic profession doesn't want to deal seriously with this issue, as I've argued at length before.

by Obey on Wed, 02/23/2011 - 5:39am

Trying to rationalize America's conversion into a frozen third-worldish oligarchy is a major growth industry with a high rate of "innovation". Well paid too.

by David Seaton on Wed, 02/23/2011 - 10:56am

Thanks Obey. I missed this comment earlier.

Had I just read further down the article, I could have displayed the US diagram--which is a less dramatic curve. Interesting that Cowen didn't display this graph, since his thesis focuses only on the U.S.

For the record, I think Cowen did address the issue of ordinary Americans to an extent. He talked about how the GDP misrepresents real economic growth, and he also addressed the growing income disparities. But he placed the blame for the latter somewhere else than I think you would--on economic conditions rather than government policy.

by Michael Wolraich on Thu, 02/24/2011 - 10:26am